Detecting hearing loss early on in a child’s life allows for interventions to be put in place so that a child’s development will not suffer. The University of Leuven has created a three-minute self-screening method for discovering hearing problems, which is now being used in schools and offices.

Hearing impairments have a significant effect on children’s development. These could hamper their ability to understand school lessons and develop language skills, resulting in poor academic

performance, derailed learning, and atypical general development. Hence, early detection of hearing loss is vital in determining interventions that would minimize, manage, or reverse the adverse effects of such a condition.

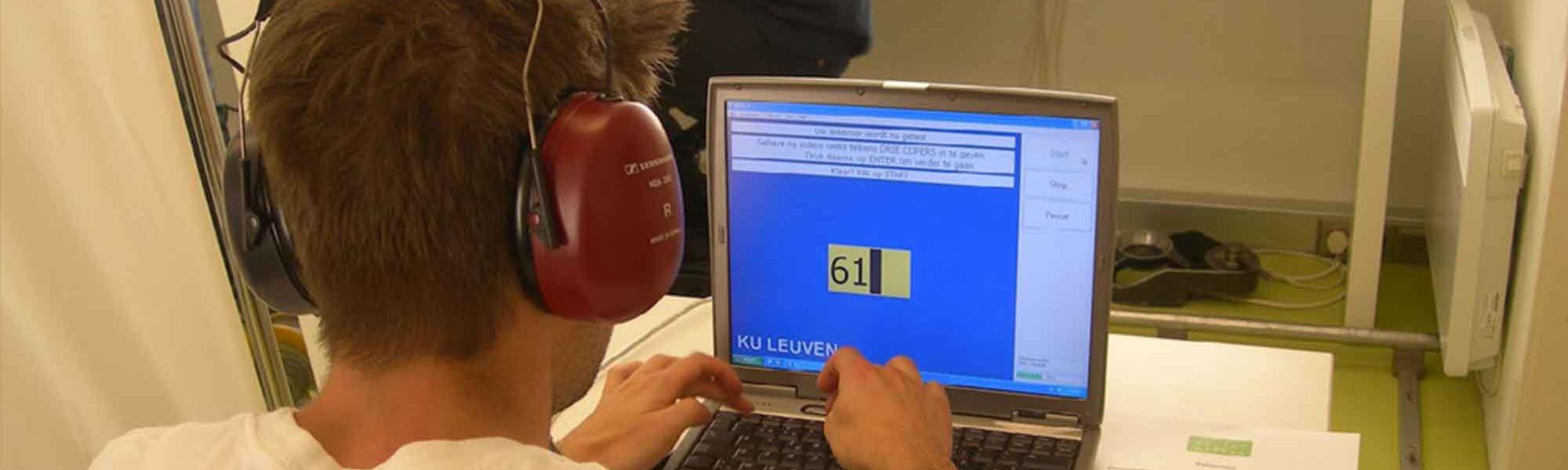

The Digit Triplet Test (DTT) is an automated speechin-noise test created for self-screening of a person’s hearing ability. The University of Leuven (KU Leuven) in Belgium developed the Dutch and French version of the test to screen children, as well as employees, for hearing problems in a fast, efficient, and effective manner that approximates situations of how a person hears in a regular environment. ‘It comes closer to the real life performance of human beings listening to speech,’ says Professor Jan Wouters of the KU Leuven Research Group of Experimental Oto-rhino-laryngology, who led the development of the DTT. ‘It’s more realistic, and that’s what it’s all about, measuring our ability to understand speech in difficult listening conditions.

3-minute test

The DTT is possibly the easiest and quickest relevant hearing test available today. It only requires a quiet room, a tablet computer with the software, and calibrated high-quality headphones. To perform the test, the person being screened would be asked to recognize speech layered on background noise. The speech consists of random combinations of three digits. Numbers are used for the speech portion of the screening because these are among the first words that children learn, Wouters explains.

During the test, 27 triplets are presented. The background noise is set at 65 decibels (dB). At first, the speech in the test is at the same level as the noise. Next, the level of the speech is adjusted to be higher or lower by 2 dB, depending on the response of the test person. If the response is correct, the test is made more difficult by decreasing the speech level. If the response is incorrect, the test is made easier by increasing the speech level.

The test is meant to determine at which level a person could still understand half of what is being said.

Within approximately 3 minutes, the person’s speech reception threshold can be determined, and the results can be used to assess whether or not the person has to be referred to experts for further auditory diagnosis.

Periodic screening

The starting point for the research for the DTT came from an intent to devise a test that would cover the way human beings receive sound in everyday life. The classic procedure in screening for hearing problems is based on detecting tones.

But recognizing tones does not necessarily translate to understanding speech, says Wouters. ‘It does not cover the real communication channels that we as human beings are developing, and that’s based on speech,’ he says.

Universal neonatal hearing screening is already well-established in many countries, and has been conducted in Flanders since 1998. It is intended to detect hearing deficiencies in the first weeks of a child’s life. In Flanders, a hearing test is also one of the mandatory medical examinations for school-age children. It is conducted at the ages of 4, 10, and 14 years. The latter is internationally unique.

In the spotlight

The World Health Organization estimates that 360 million people, or over 5% of the world’s population, have disabling hearing loss. Some 32 million of them are below 15 years old. The prevalence of disabling hearing loss in children is highest in South Asia, Asia Pacific and Sub-Saharan Africa, and lowest in high-income regions, which include Western European countries, the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Brunei Darussalam, Japan, Republic of Korea, and Singapore.

The causes of hearing loss in children could be acquired or congenital. Congenital causes include low birth weight, the lack of oxygen during birth, severe jaundice following birth, and maternal infections, such as Rubella. Acquired causes include chronic ear infections, noise, use of medicines with a toxic effect on the ears, and infectious diseases such as meningitis, measles, and mumps.

According to the WHO, majority of cases of hearing loss can be treated through early diagnosis and proven interventions.

Wouters notes that the number of children who develop hearing loss later in life may be as high as the number of children with hearing problems detected during the neonatal screening. Since

hearing problems do not always show up in the first few weeks after birth, periodic testing is important. Otherwise, normal development could be arrested by undetected hearing impairment.

‘Although neonatal screening is very important, it is equally important to check later because some reports indicate that the number of children with hearing impairment doubles in the years after birth, let’s say, the ages of 7, 8, 9 years,’ Wouters says. ‘Those children are in their full educational exploration in school and if they do not hear well, that means they are not developing as they should develop.’

Flemish funding

KU Leuven was working on the development and implementation of the DTT when funding came in from the Flemish government through the Flemish Scientific Association for Youth Healthcare at the end of 2013. While not covering the cost of the entire research and development process, the fund was used for the final evaluation of the project and the application of the software in tablet computers.

Under the agreement, the association would get a non-exclusive licence for the DTT software, according to Joke Willems, legal counsel at KU Leuven who was the technology transfer officer for the project. The association uses the DDT software to screen pupils for hearing problems.

The DTT is possibly the easiest and quickest relevant hearing test available today. It only requires a quiet room, a tablet computer with the software, and calibrated high-quality headphones.

Since KU Leuven has retained ownership of the copyright for the software, it was possible to address additional groups of potential beneficiaries, such as employees and elderly people.

Companies that focus on hearing problems and occupational health services already showed their interest in licensing the DDT software on a nonexclusive basis, explains Willems.

With thousands of students needing to be screened for hearing problems, the DTT presents an advantage because of the simplicity of the setup, the ease of use, and the swift availability of results, without sacrificing accuracy.

Unlike the classical hearing tests, it does not require a special acoustically treated room or sophisticated testing equipment. It is also less costly, and could be set up at a cost of about €1000. The test can be completed in a short time. ‘At the moment, we’re down to about three minutes per child, so that’s very efficient and with the precision of about one dB,’says Wouters.

A change by 1 dB is about the smallest change a human being can detect. The results of the test in schools can be immediately uploaded using wireless connection to a central database so that the medical team can monitor these at any time and any place, and take the necessary action. Data collected from the test, especially on older children and teenagers exposed to loud recreational sounds, can be used to set up schemes to prevent further hearing loss.

At the moment, the DTT is being used to test children between 8 and 15 years old, as well as employees, says Wouters. The university is developing the test to make it suitable for younger children also.

Medical advisory services who monitor the health of employees have also expressed interest in the test, and KU Leuven has issued non-exclusive licences to several of them, says Willems. The university charges a fee for the licence, but it is a minimal amount that just covers the cost.

As a research organization, KU Leuven does not intend to profit from it, Wouters says. It is looking for a third party partner to commercialize and distribute the test and handle related details of such a venture.

KU Leuven has been talking with local distributors, but Wouters believes that the test could also be marketed internationally to reach a bigger consumer base. He explains that it would be easy to adjust the test for other markets in other countries by changing, say, the language and the reference values.

If the DTT reaches a wider audience, more children, who are still developing into their full potential, could be saved from the adverse effects of hearing problems.

‘We need to seek out those children that are hearing impaired as soon as possible so that we can help their hearing by giving them hearing aids or training,’ says Wouters.